Pachamanca is an ancient method of making food, both tradition, and a delicacy, of the people of the Andes Mountains in Peru.

A meal of Pachamanca involves fascinating yet simple techniques to cook an awesome high mountain feast of local food including meats, starches, vegetables, and herbs.

When you’re in Peru, this is one meal experience you absolutely need to have.

Scroll down to learn all about a Pachamanca ‘Earth-Oven’ right now.

A Food of The Incas

You might think of Peru, and immediately think of all the awesome street you’ll find in Lima (of course, a day spent eating Ceviche is almost worth a trip on its own).

As soon as you leave the oceanside elevations though, there’s so much more of Peru to discover.

The food of the Peruvian Andes is incredible as well, and the first thing you have to know more about is Pachamanca.

A food that was already a tradition before the time of the Incas, a Pachamanca Earth-Oven meal is something that locals in the high-mountain areas of Peru still enjoy today.

Two Parts to This Article

In this article, I’ll first tell you about Pachamanca, how to make it, and then second we will show you how to eat it. Finally, I’ll also share some info on what to expect when you want to have this meal yourself.

Besides the food, there were so many more amazing details of high-mountain life we learned today as well. Spending time in the gracious care* of a Quechua-speaking Peruvian indigenous family is something we will never forget.

Now let’s get to the article!

**Huge thank you to Janet from Pasitos Andinos for arranging this amazing day for us!

A Powerful Food Experience

If you haven’t already watched the video from this day, you can check it out using this link here – an amazing meal, and an amazing day of life indeed – An 8,000 Year Old Meal in Peru!

I can’t emphasize enough how satisfying, how mind-blowing it was, or how grateful I am to have had this Pachamanca experience.

In honor of the memories, I have to tell a few stories (at the end), but to keep this article from being an entire day’s worth of reading, I will simply start with the food.

Enjoy!

Pachamanca

You can learn so much about the traditions and ways of life of the people here, just by watching, helping, (and of course eating), an entire meal of stone-cooking, heat-trapping, oven-roasting Pachamanca.

How To Make the Pachamanca

Life beyond the hot-stone earth-oven technique evolves over time, but both the ingredients and the method of creating this oven have been this way for millenia.

There are many steps, its a meal full of details, so I’ll do my best to keep it short.

What I hope should be quite obvious though, is that although this food does take hours to prepare, watching the steps to create Pachamanca really give so much more appreciation for the food when its finally time to eat.

Step 1 – Clearing and Opening the Earth

As the two words of “Pacha-manca” literally mean ‘earth,’ and ‘pot,’ (Quechua words by the way) the first step in the process is to open the earth, clearing and digging a shallow hole in preparation.

You can get a sense of the age of this cooking technique as the only metal tools in the entire process today are a single hoe and shovel.

Using these to dig, and then move the incredibly hot rocks (although hands were sometimes used even with sizzling-hot huge rocks!), it wasn’t until plates and bowls were in use about three full hours later that there were any other tools around at all.

Step 2 – Marinating Meat and Veggies

Now is a good time to start preparing the meats and vegetables, as they need to marinate for several hours before the oven is ready.

Soaking up flavors of cumin, black pepper, “huacatay” Peruvian black mint, orange juice, garlic, and mountain salt, the meat and veggies also soak up moisture from these ingredients as well.

Its dry-heat, and the meat and veggies would dry out without all this wonderfully flavorful and herbal moisture, adding to them as they marinade.

Pachamanca Outside of Peru

In the Northern Andes, people prefer to use pork for Pachamanca. The choice meat in these South-Eastern valleys is usually sheep (where we are, a large earth pot can easily hold an entire sheep).

Our meal today therefore was very special, consisting of beef, pork, alpaca and sheep.

Pachamance is not strictly a Peruvian food by the way, as Quechua-speaking people have been living here in the high mountains for much longer then the current country border lines. As Quechua people groups living today do mainly live in Peru though, Peru is likely the best place to have Pachamanca.

*another Andean country that eats Pachamanca is Ecuador, and ‘Curanto‘ is eaten in both Chile and Argentina.

Step 3 – Heating Volcanic Stones

Before the actual cooking can begin, the stones need to get hot – very hot.

Heating is done using wood, but just lighting a fire on top of the stones will not be nearly enough for the hours of cooking in a Pachamanca.

The ladies in charge quickly set to work arranging stones over the opening where the fire will be. Watching them quickly fitting all the smooth stones in place was over in less than 10 minutes – amazing!

Carefully, yet with such obvious skill, they do this in a way that I could only see would have me trying half a day to replicate.

The Earth Provides the Tools (Again)

Besides the tricky balancing of stones, you also need to have confidence that there will be no exploding surprises during the two to three hours of heating Pachamanca requires.

Therefore, when trusting your family feast to this hot rock style of cooking, only the hardest volcanic rocks will do the job.

You can usually find these in riverbeds, literally eroding from the mountains themselves, and so another part of the Pachamanca teamwork requires gathering of the right stones from a nearby river (and of course, carrying them all the way back home).

Step 4 – Creating the ‘Earth Pot’

Judging the temperature by a toss of water on the hot rocks, you can tell that its ready for cooking by gauging how fast the water deposits mineral content, and then evaporates, streaking the rocks white temporarily.

You’ll need to move quickly to create a bottom layer, and then place a few more hot rocks to create some basic walls, as now the ‘Earth pot’ oven is ready for cooking.

Serious Baking Skills

From what we saw, there’s really no one way of making Pachamanca ‘correctly,’ nor is there even a precise recipe for the food.

However, I can guarantee that it would take me days to complete what our friends here did in just a few hours – Pachamanca is something that people here learn through a lifetime of experience.

This is truly an entire food ceremony that the indigenous peoples of Peru cherish, and it is such a blessing to see how they are so proud to share it all with us here today.

Step 5 – Baking Layers of Food Construction

Not just heating rocks here, the cooking is no easy task either.

Usually, a large quantity of meat is the focus of a modern Pachamanca, but don’t forget that this oven is a once-open and once-closing type-device – you have to put everything else for the meal in along with the meat, and make sure its all in order.

The food will be put in order by cooking temperature, and another thing to manage is the hot rocks cooling off the entire time they are sitting outside the oven.

So now its time for the Pachamanca Recipe.

Get exclusive updates

Enter your email and I’ll send you the best travel food content.

First, the Starches and Corn

First, a variety of sweet potatoes and tubers go on, along with a dozen half-ears of local yellow corn.

A few more hot stones go on top, and then the entire basket of purple and pink potatoes (the one in the photo above).

The Pachamanca is deep, and it can hold an enormous amount of food if you make it well.

*Our party of a dozen people today will manage to eat less than half of the food in this quite average size Pachamanca earth oven – its amazing in that it makes delicious food, but is also so efficient.

Next, the Meat and Marinade Juices

The next ingredients arrive, and after the potatoes and corn goes the meat.

Placing the meats in, about a kilogram at a time, the sheep and alpaca are first, and then the chicken and beef in a second layer above.

I think you can notice too while eating, the alpaca meat really has the most char, but also the most thick, smoky flavor. Alpaca meat therefore, tougher than the beef or chicken, needs just the little bit of extra time to cook so that everything is ready together.

Hunger Pangs Arrive

A second important part here is the distributing of the remainder of marinade juices from each bowl.

Not only does the moment of the meat hissing and searing sound so refreshingly pleasing, this is also a way to get some moisture all the way to the bottom of the stones, making another source of heat distribution in the form of steam.

This is also when the hunger pangs really start to hit. Both the sound, and the smell, are amazing.

A Basket of Peruvian Black Mint

When all three layers of food are finally at rest, there are still a few more layers left to go. Seeing the amounts present in these too, is simply just incredible.

Literally an entire bushel basket* of fresh mint is next – as your nose will instantly tell – this is the ‘Huacatay’ Peruvian black mint.

I’m not sure if it’s the same species of ‘huacatay’ as the one in the recipe for ‘Cuy’ (the meal of guinea pig), but it smells similar, and looks like the ones you’ll see filling tables in Cusco markets as well.

An Armload of Bean Pods

Writing these words awhile later, its not hard at all to remember the volume of minty smells that all of this Huacatay gave off.

This final layer sort of acts like a to seal, closing a horizontal door on the oven with a dose of deep minty-crisp aromatic and cooling flavor.

**I would guess they were dropping on no less than 5 entire kilograms each of the leafy herbs and long pods of white fave beans.

Step 6 – Holding in The Heat

Finally, the Pachamanca needs a cover, and the entire mound gets a few final sheets of cotton-weave sacking. Not so much for trapping heat, this will protect the food from the dirt that’s coming next.

About 100 shovels of earth come next, temporarily returning the food to the ground from where it comes. The symbolism is clear, patting the earth on top with a final few taps, completing the prep process of a Pachamanca Earth-Oven.

Not Just a Recipe, But a Ceremony

When seeing this food’s creation as not just a recipe, but as a ceremony, this use of soil (instead of any modern product or even just more heavy blankets) is a key part of the Pachamanca tradition.

We should always be staying mindful of the land (and what it provides for us), and for many Quechua speakers, this is so obviously a very real connection with the earth.

Celebrating Teamwork

When the last clump of dirt finally falls into place, there’s a moment to relax, look around, and smile.

You can see what a time-consuming process this is, and also how, without teamwork, a Pachamanca meal would barely even be possible.

Each person has a specific role, and the entire process together allows those who take part to take pride in this Peruvian symbol of culture.

Slow-Cooking and Slowly Acclimatizing…

Taking a bit over an hour to cook, this gives us all some time to sit, sip a cup of mountain herbal tea, and enjoy the air at 3,710m elevation (12,100 feet).

This is also a great time to take a walk, if you find yourself needing to acclimatize before an Andes trek or hike. Actually, during this time our own hosts were wanting to show us more of the natural abundance around, starting out with a (short) trek to their own garden.

Quinoa From The Garden

Of all of the incredible things to grow at home, of so many things that I have never even seen before outside of photographs – the one that absolutely blew my mind just has to be Quinoa.

Although it is recently popular in the West for its health properties, Quinoa is a staple food in Andes (four thousand years of cultivation). The ancient cereal you may know is actually part of the flower of the Quinoa plant

Not in our meal here today, but in Cusco however, a delicious Quinoa beverage in Cusco, ‘maka de quinoa.’ is something I highly recommend (learn more here – link).

Tubers, and Other Colors

Next up, these are not potatoes but tubers, and our host family also grows plenty of these to trade amongst their community, or with other villages throughout a growing season.

Not only useful as seasoning in local medicinal recipes, these are also a part of making the colors for the dyes, for the weaving and clothing (more info at the end of the article).

40 Species of Potatoes

Not a typo, this family and their relatives grow an incredible 40 different varieties of potato.*

Many of these tubers they will use to trade with other families, who are growing still other crops, in the area and hills around (but also, plenty of them take part in our lunch today!).

*Peru is home to around 4,000 species of potatoes. If you’re a fan of potatoes, the Andes are surely your dream destination.

Five different types of potato are part of our lunch to be exact (and many more roots and tubers), you can see almost the entire rainbow of colors just in Peru’s potatoes.

Both the skin and the flesh of these are incredible in color, and texture, just mind-blowingly cool to see.

World’s Best Potatoes

Altogether, these are far and away the best potatoes I’ve ever had, and now I understand how the capital city of Lima is just full of some of the best french fries in the world as well.

Andean potatoes are amazing, and we are lucky to be eating them where they originate –

Right about now, the Pachamanca is ready, now its time to get back to the food.

Lunch Begins with Soup (Moraya)

Just before opening the earth oven, our hosts invite us for an appetizer of yet another amazing Andean local recipe.

One of the more genius food techniques that any human has come up with – ever – a key part of the main ingredient in this ancient soup recipe is ‘Moraya.’

Natural freeze-drying technology, using it here to keep potatoes.

In cold weather, there are very few foods that can satisfy like a hearty potato soup or stew, but this is just on another level of food genius and ingenuity.

Here’s how it works.

Ancient Peru may have been home to the world’s first potato chips

Naturally Freeze-Drying Genius

A mind-blowing technique of ancient Andean food-preparation requires only the simplest ingredients in the world.

It needs just water, and sunlight.

In the Andes’ driest months, daytime temperatures are high, and the sun is nice and fierce, hot enough to really scorch the outside of a potato and dehydrate its inside skin.

The extremely high elevation however, causes nighttime temperatures to drop below freezing, drying out whatever bits of moisture are still left inside.*

This harsh series of opposite conditions may be the world’s first potato chip process, but taking it even one huge step further is what happens when people want their dry potatoes to last for several years instead.

Andean Potato Chips Don’t Expire

Repeating the light-cold-light-cold for several few days will dehydrate the potatoes almost completely.

After removing the skin, the potatoes are put into a basket, and the basket is put into moving water.

Sitting in the cold river stream for 3 weeks, it is kept free from pests, and when everything is ready the flour from those potatoes can last for 4 years without spoiling.

Great for traveling (much lighter than entire potatoes), this food is incredible for helping humans make it through a year in areas like this of often too little, or no rain (these can supplement the daily diet).

Even today, its still great in 2019, and the knowledge makes these delicious bowls of soup all the more amazing.

You Need To Know About Tocosh

*If you enjoy eating “tocosh,” or if you saw us eating it in Lima (this clip here), you will likely know how unique, and quite infamous, this strange yet healthy freeze-dried local delicacy is…

Did you know though, how ‘tocosh’ uses up-to-1-year-old unrefrigerated potatoes? Also, just to mention it, before the potatoes are put in the cold river water, there’s a final process that involves people stepping on the potatoes, squeezing out every last bit of water, and loosening up the potato skin… its amazing, and maybe the most amazing part is that they are not just ‘food’ but they are great to eat (tocosh is delicious!)

The Learning Just Never Stops

Aside from the breakthroughs in ancient preservation technology, this soup is also just plain delicious – its impossible to not ask for a second bowl.

It also includes ‘normal’ ingredients, things that didn’t sit under a moving stream for weeks, like huge sweet orange carrots, some pumpkin, and high-mountain green spinach and hearty stalks of kale.

There are also fresh potatoes in the soup, and the texture balance between them and the ultra-dry potatoes is great. The dry potatoes almost instantly disintegrate in the soup, and the flavor is much more sweet than the sourness you might expect from something that includes such an incredible process of fermentation.

Pachamanca Main Course

Moving back now to the oven itself, the hour-or-so cook-time is finally coming to an end.

Carefully moving away the soil, and tenderly drawing back the blankets, a burst of hot air fills the entire small courtyard area with smells of smoking food flavor.

I can remember only a few times in my life when I was ever anticipating a flavor more – I can not wait to taste each level and layer of the cooking ingredients stacking inside.

Eating Family-Style, Buffet-Style

Quickly moving each item to its own plate or serving bowl, our hosts invite everyone to sit together at a long table. We are eating here, family-style, in the open grassy space beside their house.

Giving thanks both to God and to the earth, the amazing rewards of Pachamanca are finally here.

Ancient Peruvian Barbecue

In a comfortable and family-style free-for-all, everyone takes as much of each dish as they want.

There’s too much food to actually fit on the table, and so the huatia earthenware oven top has become the buffet counter for Pachamanca lunch today.

The Pachamanca is Incredible

Honestly, no matter how big your plate is, you’re going to have to go back and get seconds when there’s this much selection before you.

The gorgeously colorful variety of food is wonderful, both in appearance and in smell, there are so many things that I’m excited for and even several things I’ve never eaten before.

*As you can see in the photo, the first plate contains basically one of everything from inside the oven – I just had to try it all before going back for seconds. I’ll give a short description of each item below, but this is also how the Quechua family piled their own plates as well.

The Starches

The sweet potatoes are glorious and incredibly creamy. The outer skin peels away just using the fingertips, and there’s a satisfying puff of steam as you break open each bite.

The brilliant yellows and oranges of these potatoes’ color just never ceases to amaze me, I wish I could have more of them right now!

Choclo Corn

Another thing that flourishes here, as it is actually native to this part of the Americas, is the yellow corn, full of huge, juicy kernels.

These sweet corn kernels retain so much moisture inside that they’re almost milky.

The drier texture I was expecting just wasn’t there at all, and actually there may even have been some fatty and meaty flavors as well (possibly from the fats and juices running down into the corn as it was resting at the bottom of the earth pot oven).

A second helping of this corn is mandatory, maybe even before you’re done with the first plate of food.

The Selection of Meats

It is impossible to pick a favorite, but both the lamb and the alpaca are wonderful.

On the outer layer of each huge cut of meat, the texture is crispy, almost like a sear, as each piece has come in direct contact with at least one of the hot stones.

The original marinade of orange juice, garlic, mountain salt, black pepper, and Peruvian mint gives as incredible smell as well as flavor.

Inside the cuts of both the sheep and the alpaca though, the texture is more like meat when it is baking dry – and wow do they ever have a deep and delicious barbecue flavor from all that time in the marinade juices.

Fava Beans (or Broad Beans)

These white fava beans are a key ingredient to Pachamanca, and may also be my favorite part of the entire meal.

If you can master the trick, they’re so soft you can just slide the entire pod right through your teeth. They are so unexpectedly juicy inside.

Squeeze out all the natural pressure cooker moist bean goodness, you’ll get three to four beans per pod, and then just toss the empty casing aside before grabbing up another.

I couldn’t help but expect them to be dry, as they have such a thin skin for protection in the Pachamanca huge dry-oven heat.

Thinking back though, remember the order of the cooking, notice how the beans don’t go in with the rest of the ingredients.

They sit on top of everything, they cook more with steam than direct heat – this its whats making them so soft, and so wonderfully easy to eat as well!

Cheese

A high-altitude cold-weather delicacy around the world, cheese is also a staple food in South America (and usually the flavor profile is quite mild).

The cheese itself is nearly liquid due to having freshly come from the nearby earthenware oven, but as it is heating without actual direct heat, the taste was completely of the cheese alone (and no flavor from smoke, from a pan, etc.).

Alternate bites between the chunks of slightly dry meat, starchy potatoes, and finally the cheese. Its a mouth state of total flavor overload, but you may also be in serious need of saliva.

Adding in bites of the corn, and stripping off entire pods of fava beans, you can balance the moisture necessary to continue chewing constantly. I was past the point of speaking, and nearly to the point of not thinking.

Focusing clearly on introducing one bite after another, in a personal battle between racing through each plate, or savoring each new bite, its a meal of dreams to say the very least.

This Meal (and this Day) Are Incredible

I’m going to be honest, I could only many a few words of Quechua language today (‘Sol-pay-ki’ for ‘Thank You,’ but here’s an incredibly in-depth website). Everyone here speaks Spanish too as well, but my Spanish is not much better than my Quechua…

Sharing a meal together though is something I will never forget – constantly and consistently obvious that food can be a great uniter, such a wonderful way of bringing people together.

I have nothing but gratitude for the way this Peruvian family shares everything with us, and as the meal ends, the learning only goes on…

A Little Back Story

I just have to share some of the back story here. It’s obvious in the photo that there’s something going on with the silverware.

Silverware is (Wonderfully) Optional

The family here, kind enough to prepare at least a dozen clean sets of silverware for the meal, set them all next to the food. I see there’s at least enough for one set for everybody, but at the table, there’s no silverware to be seen.

Using only our hands, one by one it wasn’t long until we were all smiling at each other, noting the large pile of comfortably unnecessary silverware, sitting at the far end of the table. When it finally came time to eat, people one by one chose the more comfortable and convenient way of eating, and only afterwards did we all notice that each other were doing the same.

Everyone completely enjoying themselves, I think its wonderful when everyone is in agreement – sometimes there’s absolutely no need for anything but nature’s finest five-finger utensil.

Post-Meal Relaxation and Life at High Elevation

At this high elevation, nature simply forces you (by lack of oxygen in the air) to take life a bit more slowly than you would down at a lower elevation.

This works just fine, as the surroundings around this home are simply breath-taking-ly pretty to see.

There are hilltops extending away, until they’re almost out of sight. If you take a moment to look even further though, you can tell that just behind those last hills are some even higher jagged white peaks, towering away in every direction.

The air above Cusco is a remarkable color of blue, in many places though a blue that’s matching the ground beneath. The area is full of lakes, and the hilltops around are full of alternating patterns of green and straw-color brown.

This is a day I’ll remember forever, for a long list of reasons, and I would love to return to Peru’s Andes Mountains right now.

Life Besides the Cooking

A traditional meal of Pachamanca obviously requires some fairly specific and time-consuming procedures.

Therefore, when you want a meal of Pachamanca yourself, I can’t recommend anything but the real thing.

You can have Peruvian barbecue at many restaurants – and I’m sure it will be delicious – but watching the process today is for me, a huge and undeniable part of the experience.

Giving yourself time to appreciate the natural-ness of it all, also seeing in person how beautifully self-sustaining the native high-mountain people groups are here (in many more ways besides just their cooking) – its a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

No Comparison for Authenticity

If you have the chance at all, I urge you to get out of the city centers for an authentic meal of Pachamanca.

*There is actually a National Day of Pachamanca in Peru (the first Sunday in February). This will probably be the time you’ll see people (other than those living in the high mountain Andean areas already) celebrating this Peruvian food history with an amazing heritage meal of Pachamanca.

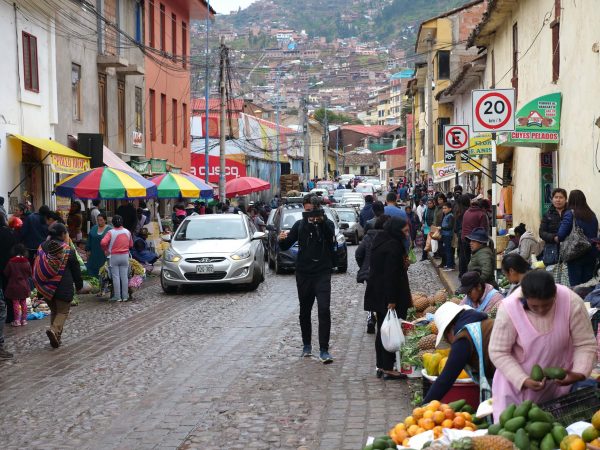

Cusco, Peru

Moving from the seaside near Lima (the capital), up to the high country near Cusco (in the Andes Mountains), you can literally watch Peru change right before your eyes.

Its incredible how things can be so different even just on opposite ends of a 90 minute flight.

Something that’s immediately obvious everywhere in Peru though, is how modern day development can only intertwine with (and never cover up) the mountain dwelling (mountain-loving) people and their history.

In so many ways, Peru is still so traditional, and wonderfully proud of their history at that. This is something that life in Cusco will very quickly help you grow to love, and this is a very special place in our world indeed.

“Pachamanca” is one of many words in use from Quechua languages

A very important part of Cusco, and of Peru, are the indigenous peoples (who almost entirely speak Quechua).

They’re still the largest indigenous group in Peru today, those who speak Quechua are the original people of this land.

Everywhere you turn, there’s a sort of confident, laid-back type of hospitality (life outside of Lima is particularly laid-back and relaxing). You had better believe the warm welcome includes every part of Peruvian people and their food.

The Culture is Obvious Everywhere

You can see their culture everywhere, in the beautiful colors, and in the language on signs. Yes, even the name of the two main foods we’re wanting to have here (both Pachamanca and ‘Cuy‘), all of it comes from the traditions of the ancient and original people of Peru.

*Some archeologists say that people in the Andes have been cooking food with hot stones for maybe as far back as 8000 years, which would then imply that people have been living here even long before that time as well.

Life In The Andes Mountains

For the final part of this article, I would like to give just a few more details about our entire experience.

I have to say a huge thank you to Janet from Pasitos Andinos Experience for arranging this amazing Pachamanca.

Of course the earth oven meal is delicious beyond belief, but what is equally as incredible to me is all the time learning about everything else that comes with it. I don’t just mean the steps Pachamanca requires to cook, I mean the steps humans require to even survive in the Andes mountains.

So Incredibly Much Still to Share

These people here are beyond incredible, they have so much to teach us.

Thinking honestly, I can’t remember another day in my life where I learned more in a single 12 hour period (although this day in Laos, and this day in Pakistan would be close).

The family here today, the mothers of this amazing family so generous to us. They’re not only taking care of us, of our food, but they’re doing it slowly enough that we could understand, and learn along the way, and gave us the enjoyment and satisfaction of eating together with us as well.

Thank You

They even finish with a chance for questions and answers, I for one, have nothing but appreciation.

Some days of life are good, other days are really, really good – thank you for giving us these memories.

Finishing with Pachamanca

For the origins of the earth oven technology, its not exactly clear which part of the world actually began to use it. I for one though, am constantly in awe, at how capable the people in all of these areas are.

Today, we are learning as they share with us things that their ancestors already knew thousands of years ago.

Speaking only about Pachamanca though, various Pacific island cultures, the area of Oaxaca in Southern Mexico, and the Quechua-speaking people of the Andes, all have different techniques of cooking using similar styles of ‘earth-pot’ ovens.

History is IN The Food

Where ever it began, all of the history IS now a part of this food.

History you can taste, is definitely a history I want to learn about.

Thanks for reading, leave a comment below if you would like to know more information, and see you for the next article!

Get exclusive updates

Enter your email and I'll send you the best travel food content.